Despite my gloomy introduction, I’ve always been tremendously optimistic about the ability of our higher education institutions to change the future.

After all, we in higher education have the privilege of working with the single biggest concentration of intelligence our country has!

If we adopt

7 Habits of Highly Effective People Stephen Covey’s habit of focusing on our circle of influence (what we can do), rather than our circle of concern (what we need to rely on others to do), we can reignite the American Dream for vast numbers of Americans!

Of course, changes to the Ivory Tower will be required. Higher education needs to take some responsibility to instigate and facilitate change. The Academy needs to become the change it wants to see in others.

For the first time in 900 years, the Academy no longer has oligopolistic control over the transmission of knowledge, as demonstrated by the

Khan Academy and Sal Khan’s thousands of video instruction clips on YouTube, and

MIT’s Open Courseware initiative.

For the Academy to remain relevant, it must become more than transmitters of knowledge. It must generate graduates who are critical thinkers and synthesizers, who can and do – as

Trevor Packer stated – employ their thinking skills to translate knowledge into action.

But even if the Academy is willing to accept its responsibility as a collaborative partner in K12 curriculum reform, the challenge will be enormous.

We need to bridge the K-12/higher education divide.

- The K-12 world has mainly been about authority and control, not results.

- Our education colleges are now seen as our institutions’ cash cows rather than creators of colleague educators.

- Higher education faculty disdain what’s being taught in their disciplines in K-12 schools, yet do little to change this sad state of affairs.

An example:

Prof. James Loewen’s revealing picture of the sad inadequacy of K12 history texts and instruction in his book

Lies My Teacher Told Me. Yet, as Trevor Packer noted, until faculty are recognized for helping their K12 colleagues, most won’t invest their time doing so.

In general, most colleges and universities don’t work effectively with elementary and secondary schools, despite their inability to successfully remediate the academic preparation of entering students in most disciplines, let alone the needed non-cognitive skills we don’t try to remediate.

Perhaps one reason for this failure of engagement is that we have competing objectives:

- Some seek authority and control;

- Others focus on job protection and salary increases;

- Most faculty are concerned with professional regard,

- research and publication, and

- creating the next generation of professors.

Will the enlightened self-interest that

David Conley mentioned – or public or political suasion – convince K12 and higher education that we must work together and agree on the primacy of one objective: Educational Equity, Excellence, and Success for All?

As

Jaime Acquino challenged last night, America’s colleges and universities educate our nation's educators and we are somewhat culpable for their shortcomings. We also educate many of our local, state, and federal policy makers, and, I shudder to think, we are somewhat responsible for their shortcomings as well.

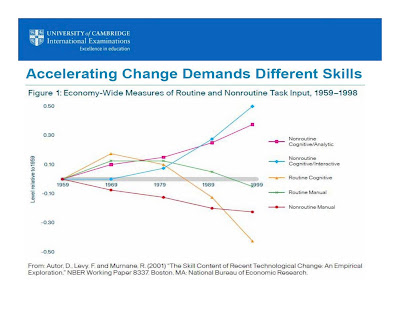

Higher education has claimed to be about developing critical thinking and synthesis abilities in our students. As we’ve heard throughout this conference, we need to be about more – about nurturing dispositions and the ability to act effectively on the knowledge we have imparted.

As

Allison Jones and

Christyan Mitchell noted, we need to define what students need to be life-ready and help them acquire these skills. We also need to help politicians, as Doug Christiansen mentioned, by declaring the achievement level required – cut scores on assessments – to do college-level work.

If “it takes a village,” we need to get out of our ivory towers and work with others in our villages to define and develop the needed knowledge and skills, attitudes and beliefs, motivation and behavior for many, many more to succeed.

We need to get beyond eduspeak and express cognitive and non-cognitive standards in terms students and their families can understand. If we want them to take responsibility for their own education, standards need to pass the “refrigerator test”: be in language and succinct enough to put up on the refrigerator door, so students and their families can work on and monitor their attainment progress.

As a former businessman, I was heartened by

Carolyn Adams’ observation: Educators need to work with the employers of our villages. For when we do, we’ll find their standards for career-ready employees are the same, academically, as those for college entry. Actually, as Patrick Killonen just reported, recognized workforce needs are

greater than those for college entry, since workers must have non-cognitive skills and dispositions not required to enter college:

- Interpersonal skills such as teamwork – which, as I noted yesterday, schools call “cheating” – and

- Intrapersonal characteristics, like integrity – in an era in which 70% of high school graduates admit to have cheated in school.

Getting American education out of our death spiral will take far greater wake-up calls than a former chancellor can muster. Perhaps the cries of public opinion and a greater exposure to the new realities from respected members of the media can help.

With that hope, I’ll turn the session over to Scott. Thank you.