As Chancellor of the Ohio Board of Regents (the state coordinating board for Ohio’s public and private colleges and universities), I lived at the interface among the worlds of K-12, higher education, and politics, so I’m delighted to reiterate some of what I learned from our conference speakers and participants, to offer a few observations of my own, and to hear those my fellow panelist, Scott Jaschik, representing the Fourth Estate of the press and media.

Before getting into the topic, however, I need to ask: Why change? Harry Brighouse kicked off this conference with his though-provoking challenge regarding the purpose of education. Yet mine is a serious question, because in many ways, the school curriculum fundamentally hasn’t changed for about 100 years.

Indeed, our agrarian school calendar hasn’t changed for over 200 years, despite the fact that less than 2% of our population – and virtually no kids – work on farms and many students lose 70% of what they’ve learned in the school year during their summer breaks.

Despite the local control authority of over 10,000 school districts, our industrial one-size-fits-all model of education has persisted, in the face of students who learn different subjects better at different times and in different ways – the age-graded instead of ability-graded system that Morgan Polikoff mentioned yesterday – and of cognitive research that has found that our model successfully educates mainly the 25% of students who are abstract learners but not the 75% who are contextual learners.

Why do we continue to educate kids for our past, instead of for their future?

NY Times columnist Thomas Friedman wrote so persuasively on the impact of globalization and the Internet in The World is Flat – now almost 7 years ago. He brought popular attention to the fundamental sea changes that have occurred in the past decade.

At this conference 2 years ago, I noted forces driving change because of state policies. Since then, the impact of the Great Recession has settled in.

Per capita state funding in constant dollars for public colleges and universities has shrunk to its lowest point in 25 years and hefty increases in tuition has barely kept resources level, in the face of the highest enrollments in history. [SHEEO SHEF 2010]

Yet things continue not to change much, driving higher education further down the death spiral I described then of inadequate higher education funding resulting in graduates without the requisite capabilities to produce growth, leading to economic and social decline, producing further shortages in funding for education.

As one who has been tweeting the pearls of wisdom I’ve picked up during this conference, I am hopeful that a tipping point of public understanding on the critical need for dramatically improved educational outcomes may come about through the social media.

It has become clear to most Americans that the objective of making students college-ready is critically important economically – since an educated populace is the key to winning in a world of global competition, and a knowledge and creative economy – and continues to be the main defender of a free and democratic society. But it’s also becoming clear that we need to re-ignite the American Dream that Jaime Aquino spoke of so passionately last night – of enabling future generations to do better than the current one, socio-economically.

On the political scene, I see a continuing building of the Perfect Storm. Because of a muddling economy in most states and communities, there will be a continued inability and political unwillingness to invest what’s needed to dramatically improve educational attainment with 100-old strategies, techniques, and attitudes. Further, increased public demand will pressure politicians to transfer the heat they’re feeling, resulting in their demanding better performance and greater accountability for results, while at the same time, they continue not to invest more in the education of our children and adults.

The educational establishment will continue to do what it’s proven itself best at doing: resisting change. Millions of the K-12 teachers and college and university professors who will be retiring in the next several years will deny there’s a need to change, hoping to ride out this perfect storm until they retire.

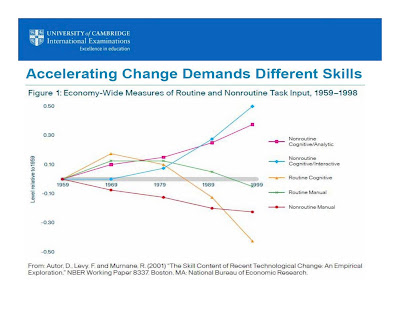

Tristian Stobie’s graph yesterday Accelerating Change Demands Different Skills reminded me of Al Gore’s graphs in An Inconvenient Truth. Yet educators seem to be very much like those who deny global warming and their need to do something to contribute to a solution. Where is our Union of Concerned Educators, crying for action by our own colleagues to rescue our future?

So what hope is there for change? Will the Academy recognize higher education’s responsibility for school reform?

(continued ➛)

(continued ➛)

No comments:

Post a Comment